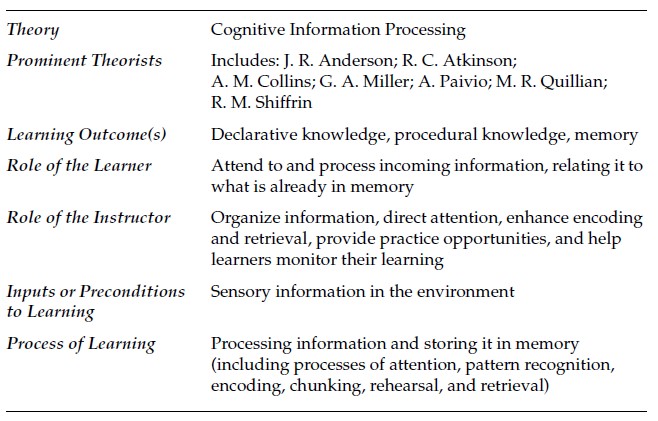

In cognitive psychology, humans are seen as a data processor, similar to how a computer receives data and processes it according to a program to generate an output. It rests on the assumption that a sequence of processing systems transforms the information received from the environment. The processing system converts or alters information systematically. The goal of the research is to identify the processes and structural elements that underpin cognitive performance in order to improve it.

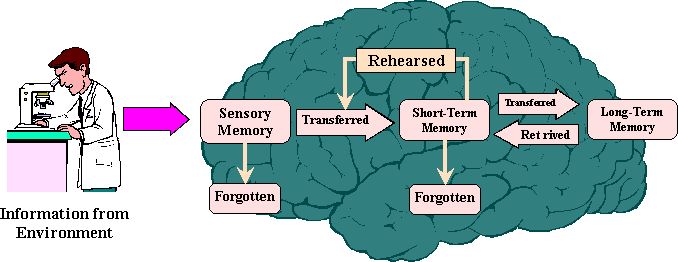

Information processing theories are concerned with how people pay attention to external events, encode information to be learned and link it to knowledge already stored in memory, retain new knowledge in memory, and retrieve it when necessary. Consequently, learners are seen as information processors who actively seek and process information. The proposed method, in contrast to Piaget’s theory, posits that cognitive development is continual and progressive, rather than being arranged into discrete phases. Sensory memory, short-term memory, and long-term memory are the three stages of memory proposed by CIP.

Information Processing: Sensory Memory

Sensory memory is linked to the senses of vision, hearing, and feeling. Sensory memory functions to store sensory information in memory for a short period of time, just long enough for it to be processed further. Each of the five senses has its own sensory memory, although it’s supposed that they all work in the same manner. Sensory memory is briefly restricted while dealing with visual stimuli. This indicates that a lot of visual information is registered, but it decays quickly if not processed further. Auditory information, by contrast, lasts longer in sensory memory. This is thought to be due to the length of time it takes for speech to be processed. Echo is the name for auditory data.

Sensory perceptions are influenced by both our prior knowledge and the circumstances in which we encounter them. We’ve all experienced how selective our attention can be. We may be reading a newspaper and watching TV at the same time. We suddenly understand that the news report is only a continuation of the tale we read in the newspaper. We come to a halt to listen. We were already aware of the material since we had just read it, so we paid attention to it.

The importance of context in language comprehension is evident. The term “tape,” for example, has numerous meanings. “I need to wrap a birthday present—do you know where the tape is?” I could say. Most listeners would immediately recognize that I’m searching for a roll of sticky tape rather than a video or audiocassette.

You’ve probably had the experience of running into someone you’d know in one area of your life (for example, if they work in the same office or building) but not in another (for example, at your daughter’s soccer game). You may be aware that you are acquainted with that someone, but you are unsure why or who they are. This is a contextual problem.

Information Processing: Working or Short-Term Memory

A sensory impression is stored in short-term memory, also known as working memory, once it has been recorded. Short-term memory seems to have a rather restricted capacity. In short-term memory, we can only store roughly 7 “chunks” of knowledge at a time. Of course, chunk size is relative rather than absolute. We could have problems managing 7 single words in a foreign language, yet we might be able to handle 7 phrases in our own language with ease.

The difference is that unfamiliar words have no meaning for us, but sentences in our own language have, and hence do not take as much mental effort. Earnings should be arranged such that the student can chunk activities effortlessly. The current theory is that when new chunks enter memory, chunks that were previously filling accessible spaces in working memory are pushed out.

Information Processing: Long-Term Memory

Long-term memory is referred to as a “permanent record” or “knowledge storehouse.” It is presently considered that knowledge is never totally lost after it has been integrated into long-term memory. Long-term memory is capable of storing an infinite quantity and diversity of data. However, we forget things because the connection to the knowledge has weakened, not because the information has been lost. There are certain fundamental principles in long-term memory:

Declarative knowledge vs procedural knowledge. Declarative knowledge entails being aware of the fact that something is true – that A is the first letter of the alphabet, that Ankara is Turkey’s capital. Declarative knowledge is conscious; it is often expressed verbally. Declarative knowledge is metalinguistic knowledge or information about a linguistic form.

Procedural knowledge, on the other hand, entails understanding how to accomplish something, such as driving a car. We may be unable to describe the process. Procedural knowledge includes implicit learning, which the learner may be unaware of, and may include the ability to employ a certain form to comprehend or generate language without being able to explain it.

Verbal and imaginal representation in memory. Concrete words (those to be portrayed easily) tend to be recalled more than abstract terms. For instance, it seems to be easier to recall words like “car” or “bicycle” rather than “envisage” or “imagine”.

Retrieval. The distinction between “recall” and “recognition” activities is critical in education. You may have enjoyed multiple-choice examinations as a student. Why? Because they often demand merely knowledge of a phrase or meaning, they are far simpler cognitively than essays, which frequently entail free “recall” activities.

Encoding Specificity. The greatest retrieval cues are the same ones that were utilized to encode the information. Imagine any figure on a topic that depicts the theory-building process? Assume I told students that they needed to remember it for an exam. According to the notion of encoding specificity, it would be simpler for you to replicate the steps in that chart if I offered you a blank version that looked precisely like the initial chart rather than just telling you to list the seven stages. This is because the chart’s shape acts as a retrieval cue for the data.

Forgetting. Some theories posit that once something is stored in long-term memory, it is never totally “lost” (unless the brain is physically damaged). If that’s the case, then when we forget anything, it’s either because the knowledge was not encoded at the beginning, or because it’s still there but can’t be recovered.

The home address that we usually use has vanished from long-term memory. My family’s address, which I remember from when I was a kid, is undoubtedly still in my head, but I can’t find it. Because of all the addresses I’ve had to learn and remember since then, this number is likely to have suffered from retroactive interference. It’s also possible that we’ve misplaced the information, similar to misplacing a card in the traditional card catalog library organization method. The book is still on the shelf at the bookstore; you simply won’t be able to locate it.

Implications of CIP for Learning

Organize your instruction. Graphic representations have been shown to be especially useful in aiding information encoding and memory storage. The use of graphic tools in gaining structural information, which displays connections between ideas in a content domain

Arrange a wide range of practice opportunities. The purpose is to assist the learner in generalizing the idea, theory, or technique so that it may be used outside of the context where it was first introduced.

Assist students in becoming self-regulated. Help students in choosing and implementing effective learning tactics including eliciting and questioning.

Recognize the limitations of short-term memory. Make use of the chunking concept. Instead of presenting 49 individual things, divide them into seven groups. Make use of elaboration and a variety of circumstances.

Limitation of CIP Model

The human brain’s analogy to a computer is relatively restricted. Our capacity to acquire and remember knowledge as humans are influenced by a range of things, ranging from our degree of desire to our emotions — characteristics that have no effect on machines. Computers also have the finite processing power, however, human memory capacity is limitless. Humans, on the other hand, have an enormous ability for parallel processing or digesting numerous bits of information at the same time.

Please feel free to contact me if you need any further information.