Motivation is a controversial concept as it is not possible to measure it directly. According to psychologists working in the field of education, motivation is a term that highlights the process of using our energy to conduct purposeful behavior (Wlodkowski, 1989). There are several definitions of motivation. The majority of these definitions are divided into two groups: physiological and psychological definitions. However, In the broadest sense, motivation refers to the process in which individuals interact with the environment in a way that their behaviors are driven by goal-seeking desires.

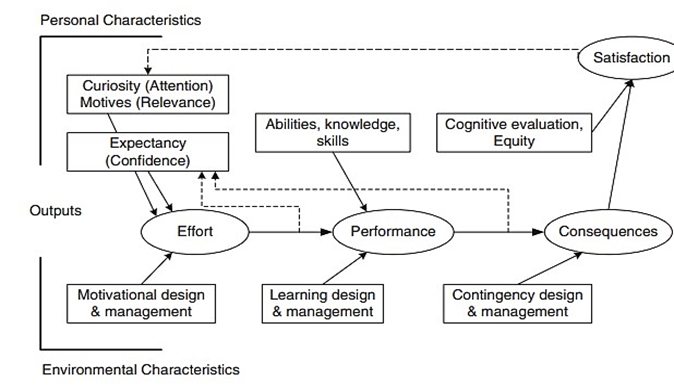

Studies on motivations aim to understand individuals’ deep feelings about why they desire to do these behaviors. There had been many answers to this question by the authors, philosophers, and psychologists. Some theories grounded on psychology and neurology were thus put forward to explain the phenomenon. Behavioral approaches, cognitive science, and emotion, on the other hand, have been investigated to understand the dynamics behind motivation. By taking a holistic approach, Keller (1979) came up with a model of motivation and performance based on the system theory to explain the measurable outputs of motivation, psychological attributes which affect motivation, performance, and attitudes of individuals, and environmental factors on the goal-directed behaviors.

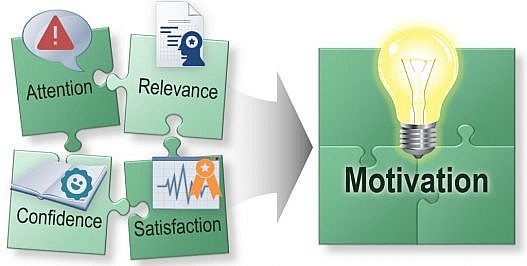

Additionally, the elements of the ARCS model (attention, relevance, confidence, satisfaction) that propose strategies to promote motivation exists in the model. The motivational component is especially significant since it affects basic judgments of individuals about whether to take responsibility for a task and pursue a certain goal. No other factors make sense unless this behavior is initiated (Bixler, 2006).

Figure 1. The Model of Motivation of Performance of Individuals (Keller, 1979)

The model clearly depicts how motivation can affect the effort and performance of individuals towards reaching a goal by integrating their current knowledge and abilities. It also illustrates to what extent the amount of curiosity and relevancy influences motivation. This model is considered as one of the earliest frameworks that provide information and strategies on how to enhance the design process with motivational elements.

Since the emergence of this model, there has been an exponential growth in analyzing the motivational factors that influence the instructional design (Keller, 1983b; Wlodkownski, 1999; Brophy, 2004; Keller, 2008b; Deimann & Bastiaens, 2010). The rich body of investigations thus produced concrete and sound implications for the instructional designers.

Firstly, motivation to study is increased when a learner’s attention is sparked as a result of a perceived gap in present knowledge, and the target information or skills to be learned is believed to be significantly connected to one’s goals. Relevance is influenced by perceptions of applicability or authenticity in a learning exercise, although these are not the only factors. Relevance could also be established by generating meaningful challenges, particularly for those with strong achievement demands, and allowing them some power over choosing their objectives and the methods of achieving them (McClelland, 1984).

Secondly, learners are more motivated to study once they feel they are capable of mastering the learning task. People who do not have good expectations for achievement or who are not able to overcome setbacks and disasters over which they have no control might have sentiments of helplessness. This situation describes individuals who are convinced that they would fail at a task despite having the capability to succeed if they invest enough effort. This problem might be handled using techniques that assist pupils in attributing the consequences of their actions to their talents and capabilities rather than luck or uncontrolled circumstances (Bixler, 2006).

Thirdly, learners are more likely to be motivated to learn when they expect and experience positive consequences from learning effort.

Last but not the least, learners’ motivation to learn is reinforced when they use self-regulatory measures to preserve their goals. It is controversial whether learners usually take a direct path from goal-setting to goal-attainment. Rather, learners pursue numerous goals that include not only learning but also a range of good experiences. As a result, several goals interact in complicated ways and vary over time. Thus, using self-regulatory strategies could enhance keeping the motivation to study or work.

Reigeluth (1999) posits that there has been an ongoing transformation in instructional design towards a learner-centered and active learning environment. In line with this shift, motivation appears to be a component of the new instructional design theories. There is ,however, insufficient emphasis on the importance of employing suitable motivational strategies (Keller, 2008b). This could be improved with the integration of motivational concepts.

The attempts to develop applicable motivational frameworks are not new, but the emphasis has shifted. While earlier models focused on a single motivating element, more modern ones attempt to combine a wide range of significant ideas in a holistic manner such as Wlodkowski’s time-continuum model (1999) and Keller’s ARCS model (1984).

Wlodkowski categorizes motivational strategies and specifies when they should be used in the instruction. Teachers are responsible for choosing a certain type and number of strategies from the model. The ARCS model likewise includes motivational strategy and tactic categories, but it also includes a systematic design process that involves an examination of learner motivation to choose the quantity and types of relevant tactics to integrate.

The ARCS design process contains ten phases that range from analysis through design and development to assessment (Keller, 2010), and it combines well with lesson planning and instructional design procedures. The process starts with gathering the necessary information on the lesson that needs to be improved, as well as the teachers and students. It then moves on to an examination of the target learners and existing course contents. Based on this information, the designer or instructor can specify and integrate motivational strategies. Therefore, it could be said that both models aim to provide hands-on guidelines and ideas on how to enhance the instructional design with motivational attributes.

In conclusion, this paper investigated motivation and its relationship to instructional design and technology. The above-mentioned motivational models were explained briefly and the implications for instructional designers and instructors were highlighted. The following themes emerged from this article:

- Gaining and maintaining the learner’s attention is a critical motivational requirement. The contents must be visually attractive and delivered in a variety of formats. This will spark your sensory curiosity. Activities should be demanding but not impossible to do.

- The learners should understand the value of relevance of the lesson to their goals. Goals that are explicitly outlined will assist the development of relevance since the learners are more likely to grasp the expectations. It is also significant to activate the prior knowledge of the target audience by integrating relevant examples or activities.

- Learner confidence could be built by employing precise rules and processes, clear learning samples, meaningful feedback and establishing secure learning environment in which there is a good degree of challenge. The instructors must make an impression that all the learners should feel there will be help when needed.

- It is worthwhile to establish enjoyable learning experience which will increase the satisfaction of the learners. Learners should take more responsibility over their own learning. Despite the view that students do not get engaged with over responsibility, it should be balanced to keep control. The fantasies could be used to increase satisfaction, raise self-esteem, and connect the current instruction with the previous experience.

- Developing a real life like learning environment will enhance the authenticity and contextual learning. This thus will increase the attainment of target goals.

References

KeIIer, J. M. (1987). The systematic process of motivational design. Perform. Instr, 26, 1-8.

Wlodkowski, R. (1999). Enhancing adult motivation to learn (Revised edition). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass Inc.

Bixler, B. (2006). Motivation and its relationship to the design of educational games. NMC. Cleveland, Ohio. Retrieved, 10(07).

Keller, J. M. (1983b). Motivational design of instruction. In C. M. Reigeluth (Ed.), Instructional design theories and models: An overview of their current status. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Keller, J. M. (2008b). An integrative theory of motivation, volition, and performance. Technology, Instruction, Cognition, and Learning, 6(2), 79-104.

Deimann, M., & Bastiaens, T. (2010). The role of volition in distance education: An exploration of its capacities. International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning, 11(1), 1–16.

Brophy, J. (2004). Motivating students to learn. Routledge. Keller, J. M. (1979). Motivation and instructional design: A theoretical perspective. Journal of instructional development, 2(4), 26.

Please feel free to contact me if you need any further information.