Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs) have lately gained a lot of interest from the media, entrepreneurs, educators, and members of the technologically savvy public. The promise of MOOCs is that they would give open access to cutting-edge courses, possibly lowering the cost of a university degree. This is somewhat contradictory to the conventional higher education system. This has also promoted prestigious universities to make their courses available online thru platforms such as EDx or Coursera.

Along with famous institutions, new commercial start-ups like Udacity have also been formed, providing online courses for free or charging a nominal cost for certification that is not part of the credit for awards. Larger firms, like Pearson and Google, are also intending to enter the HE sector as global players, with a MOOC-based approach likely to be part of their strategy. The Open University in the United Kingdom has created Futurelearn to bring together a variety of free, open, online courses from premier UK institutions for learners all around the globe (Futurelearn, 2013).

Following the growth of Open Educational Resources, Dave Cormier used the term Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs) to refer to Siemens and Downes‘ “Connectivism and Connective Knowledge” course in 2008. This online course was originally meant for a group of twenty-five enrolled, fee-paying students interested in studying for credit, but was later offered to all registered learners. As a consequence, over 2,300 individuals enrolled in the course for free or earned credit. In 2011, Sebastian Thrun and his Stanford colleagues offered access to their university’s “Introduction to Artificial Intelligence” course, which drew 160,000 students from more than 200 countries and territories. MOOCs have become a catch-all term for various contemporary online course initiatives launched by universities, individuals, and commercial organizations.

The History of Massive Open Online Courses

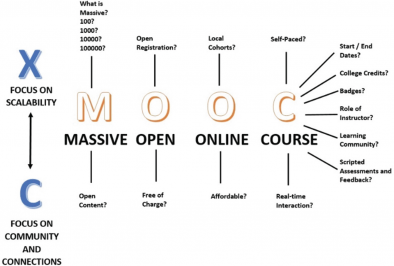

The initial goal of MOOCs was to open up education and give as many students as possible with free access to university-level instruction. In comparison to regular online university courses, MOOCs have two distinguishing characteristics:

- Open access: anybody may take a free online course.

- Scalability: courses are created to accommodate an unlimited number of participants.

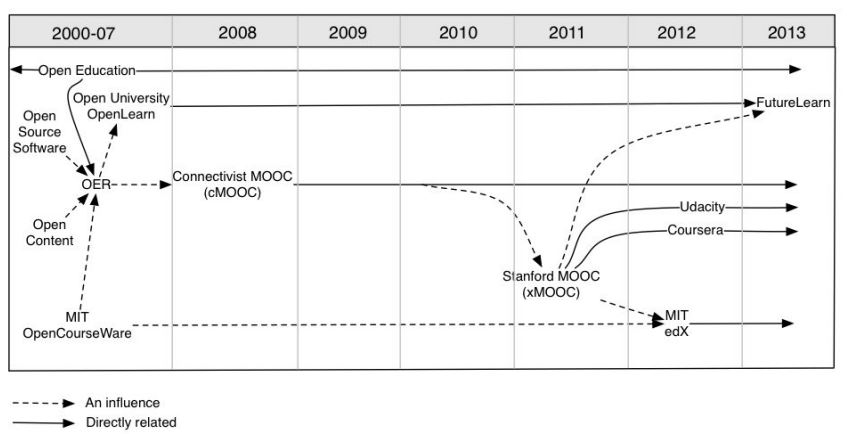

MOOCs are anchored in the values of open education, the belief that information should be freely disseminated and that the desire to learn should be addressed regardless of demographic, economic, or geographic barriers. As seen in Figure 1, the notion of openness in education has evolved fast since 2000, despite its early twentieth-century beginnings (Peters, 2008).

The Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) launched OpenCourseWare in 2002, and the Open University launched OpenLearn in 2006, demonstrating the open education movement’s continual evolution. Numerous open learning platforms have been established by top schools as a result of the early development of MOOCs; examples from 2012 include MIT edX and the Open University’s Futurelearn. A crucial message that emerges is that the expansion of MOOCs is resulting in an increase in market participants as higher education institutions and commercial organizations attempt to capitalize on these advancements in online learning.

xMOOCs and cMOOCs

Different philosophies have pushed MOOCs in two separate pedagogical paths: connectivist MOOCs (cMOOCs), which are based on a connectivist learning and use informal networks to facilitate learning; and content-based MOOCs (xMOOCs), which take a more behaviorist approach. This is, in many respects, the same discussion about learning method vs learning content that educationalists have been having for years and have yet to settle.

cMOOCs place a premium on linked, collaborative learning, and the courses are organized around a community of like-minded ‘participants’ who are generally unrestrained by organizational restraints. cMOOCs enable the exploration of novel pedagogies outside of typical classroom settings and, as such, tend to reside on the extreme edge of higher education. On the other hand, the instructional model (xMOOCs) is simply a continuation of the pedagogical models used inside universities, which are arguably led by “drill and grill” educational techniques including instructional videos, brief examinations, and assessment.

According to the study by Margaryan (2015), cMOOCs scored higher on the following aspects:

- the criteria of authenticity of learning activities and resources

- measurability of learning objectives

- activation of prior knowledge / skill

- application and integration of new knowledge skill

- collaboration with and learning from other participants

- contributing to collective knowledge

- accommodating learners’ preferences

xMOOCs slightly outperformed cMOOCs in terms of

- the organisation and presentation of course material

- learning activities that require learners to broaden their range of collaboration by working with others outside the course rather than only teaming up with other course participants.

Quality assurance of MOOCs is a significant challenge for higher education institutions. In most situations, as compared to other online courses, MOOCs lack structure and seldom include a lecturer or educator as a major figure. They are generally self-directed learning experiences, which are somewhat distinct from traditional education. Due to the open nature of MOOCs, they attract an audience that is self-selected to be interested and enthusiastic about this kind of education. MOOCs need participants to have a particular degree of digital literacy, which has prompted issues about inclusion and access equity.

References

Please feel free to contact me if you need any further information.